Mathemagical Tricks

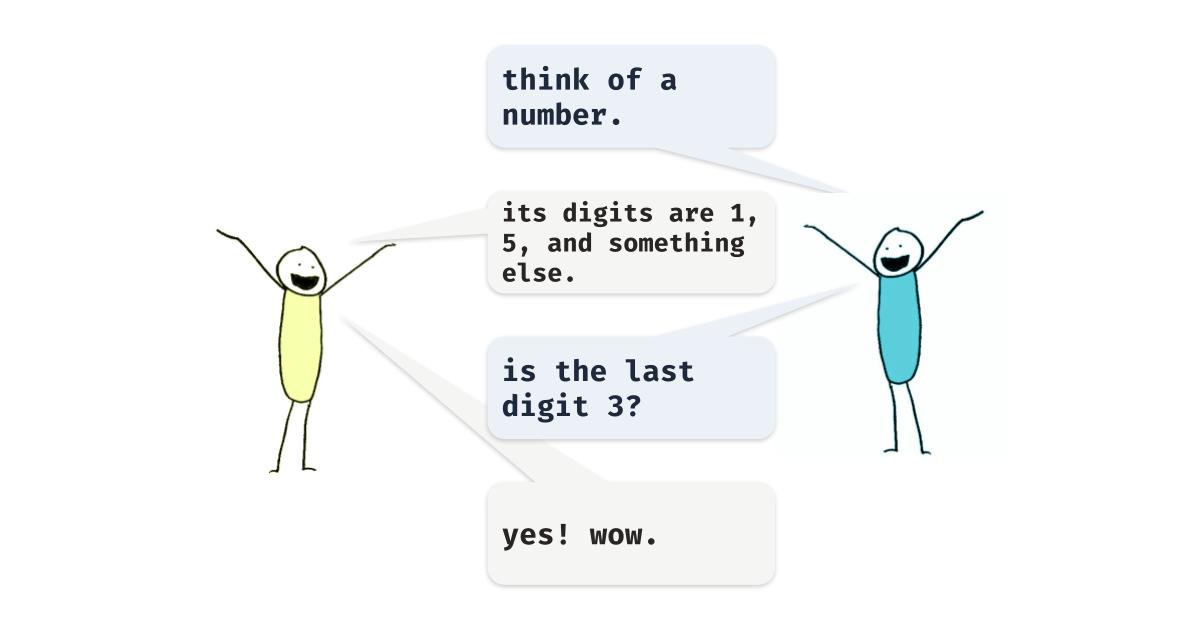

Guess the missing digit of a friend's number.

Have you ever wanted to convince your friend that you have psychic powers? In this article you’ll learn how to use amazing mathematical principles to help you on your noble quest.

Performing the Trick

- The first step is to ask your friend to think of a 3-digit or 4-digit number.

As an example, we’ll use the number

5832. - Then, ask your friend to shuffle the digits of their number randomly. For

example, we might shuffle to

3852. - Tell your friend to subtract the two numbers. For example, we might perform

5832 - 3852 = 1980. - Ask your friend to say all of the digits in their result except one. For example, we might say 1, 9, and 0.

- In your head, add the digits together. In our example, we get

1 + 9 + 0 = 10. - Find the next multiple of 9. For example, the next multiple of nine after 10

is

2 * 9 = 18. - Subtract the numbers from steps 6 and 5 to get the remaining digit of your

friend’s result. For example,

18 - 10 = 8. - If your result from step 7 is 0 or 9, guess 9. If they say it was wrong, say you were kidding and guess 0.

Examples and Practice

My digits are 5, 8, and 3. What is the last digit?

My last digit should be 2 because the nearest multiple of 9 to 5 + 8 + 3 = 16

is 18, and 18 - 16 = 2.

My digits are 2 and 3. What is the last digit?

My last digit should be 4 because the nearest multiple of 9 to 2 + 3 = 5 is 9,

and 9 - 5 = 4.

My digits are 5, 7, and 6. What is the last digit?

When summing the digits, we directly get a multiple of 9 because

5 + 7 + 6 = 18. This means that the remaining digit could either be 0 or 9,

and it’s up to you to come up with a clever way to tell your friend.

Why Does This Work?

Our numbering system has a curious feature that lets you find out the remainder of dividing a number by 9 by simply summing the digits of a number, also known as taking its digital root. For example, has a remainder of which transforms to . Because shuffling the digits of a number doesn’t alter their sum, it consequently doesn’t change the remainder by 9.

We can write any numbers as a multiple of nine plus some remainder like so: . Shuffling the digits leaves us with the same remainder , so the shuffled number will be . Subtracting the two yields

which is a multiple of 9. Because it’s a multiple of 9, the divisibility trick for nine shows that the remainder is also a multiple of 9. Since a digit can only be from 0 to 9, the sum of the digits may only go down to the previous multiple of 9, allowing us to guess the difference. This also explains why we have to guess 0 and 9 if the sum is a multiple of 9, as we’re not sure whether the person subtracted 9 from their digits or stayed by subtracting 0.

Why do Digital Roots Work?

A field of math known as modular arithmetic was created specifically for working with remainders. In this system, we say numbers are congruent modulo some divisor. This means that both numbers have the same remainder when divided by our divisor. For example, because dividing 10 and 1 by 9 yield the same remainder. Repeating this, we can also find that for any .

You can write any positive integer like so, with each letter accounting for a digit of the number: . In algebraic notation, we would write this as . Without loss of generality, we can also write this as . Setting this equal to a remainder modulo 9 and simplifying using properties of modular arithmetic, we get

Theoretically, we could perform the same nesting tactic on a number of any size and get for a 5-digit number or for a 2-digit number, showing that the remainder when divided by 9 is the sum of a number’s digits.